Thank you to readers and subscribers from last week! Your support means a lot; I came back for a second article! The more I put into this, honestly, the more fun it is. I guess it’s like anything, isn’t it.

A review of the format:

The Preface - A short anecdote.

The Idea - An applicable concept.

The Action - An example of how the concept can be applied.

I want these to be useful for you, reader. Remember: knowledge is lovely, but what matters is what you do with it.

THE PREFACE

“I really don’t like raising my hand.”

It was a common sentiment in my classroom that year. Students felt shy, uncertain, and apprehensive about sharing their thinking in the classroom. This student in particular did fine when talking to me personally one-on-one, but there was something about the context of speaking in front of the entire class that elicited such a response.

“That’s really sad. We’re all here to learn from each other, you know? Your ideas could really help other people.”

And it’s true. That’s why we come together as a class to learn, isn’t it? As opposed to sitting at home in front of our computers and learning on our own? Class is a communal thing, and we do it together. We learn together. Collaboration is key for an engaging and meaningful learning environment.

Eventually I got down to the bottom of it. Why was it that a large section of my students didn’t feel comfortable about answering questions in front of the class?

“She would yell at us if we got it wrong.”

“I felt really stupid when I made a mistake.”

It became pretty clear pretty quickly. A teacher in the previous year’s grade level team was celebrated for having high test scores in her classroom. These were her kids. Each of the students who reported having a negative attitude towards sharing their learning in front of the class had come from her homeroom.

THE IDEA

I want to write about leadership today. Namely, I want to write about places of leadership- from where do leaders lead? The more I think about this topic, the more I realize how much there is to unpack. I think about this mostly when I think about teachers as leaders of their classrooms, but I believe it can also refer to how managers and administrators work with their staff.

What I mean by this is- in the case above- the teacher who had achieved tremendous academic growth had, in effect, led her students from a place of fear. Fear of consequence, fear of belittlement, fear of embarrassment. Look, it’s effective, and I’ve met an incredibly small number of teachers who haven’t, at some point, fallen back on the good ol’ “you have a choice, you can start your work or I can (insert consequence here”). It never feels good, for the teacher or the student, but it is instinctive for a lot of folks. I’ve had to deal with this from managers and supervisors, too, who have made various empty threats or paraded around consequences. The coaches who rely on these strategies tend to lose the locker room.

Some teachers (and managers) lead from a place of authority. When I talk about this, I think about the teachers who so bravely work with the younger students- preschool, kindergarten, first grade- where using logic and reason with children is especially difficult, and “I’m the adult here, and I’m going to show you what we’re doing today” is a viable strategy. “I’m bigger than you, and I say we’re engaging in a literary analysis of The Lorax today.” Some contexts call for it, but I can’t imagine “because I said so” is super fulfilling for the leader. Often times, it’s frustrating for their loyal subjects as well.

A lot of leaders, sometimes the best ones, I think, lead from a place of expertise. One of the best leaders I’ve ever seen in a school led from a place of “I know a heck of a lot about teaching students how to read for detailed information, I’m going to show you how it all works.” Thank you, Meghan, for some of the most thought-provoking and useful PD I may ever receive. I’ve seen a lot of LinkedIn business bloggers call this “servant leadership,” with the leaders establishing their base of leadership from a place of usefulness. I really like this one, and I find it to be one of the more practical. It also feels good.

Apparently Servant Leadership Theory got its start in 1977 when AT&T executive (and totally not a D&D druid) Robert Greenleaf wrote an article about a leadership style emphasizing the needs of the team above their own needs. It’s amazing what you can find if you Google for it. I don’t know enough about this theory explicitly to say that’s what my idea of leading from a place of expertise is, but it seemed tangentially related so it’s here now.

And, at the other end of the spectrum, we have the idea of leading from a place of love. “I am here to help you, guide you, and make sure you’re well. I want your success and your happiness. I want you to understand that these two things do not need to be at odds with each other.” To me, this is leadership that moves beyond simply being useful to someone, but instead considers the wellness of that person. “If anything gets in the way of your learning, you let me know and we’ll figure out how to get rid of that obstacle together.” Unsurprising, this feels amazing.

Why all of the talk about how it feels? Yes, stoicism is cool now, and yes, everyone’s supposed to ignore how they’re feeling and pretend it’s fine. I will tell you, though, that productivity and learning is all a lot more effective when you don’t have to worry about pretending that you’re not miserable.

It’s like I wrote in last week’s post, “The Importance of an Interdisciplinary Mindset,” which proudly displayed the Raph Koster quote “Boredom is the opposite of learning.” The idea that fun is a motivator for action, and that fun is largely derived in the game-space from attempting to mentally master a puzzle based of rules and systems, shows us that misery-free learning doesn’t end. It reminds me of a conversation I had with one of my chess protégé students.

“You got better at chess. Way better. How did you beat me?”

“I don’t know. I didn’t study.”

“Nonsense. You’re saying things like ‘I lost too much material.’ Are you watching YouTube videos on the London and Caro-Kann openings like I suggested?”

“I watched, like, four hours of Gotham Chess yesterday.”

“SO YOU DID STUDY. YOU LIAR.”

Another student told me that he hates learning. By the end of the week-long special course I taught, he couldn’t stop working on his project. He couldn’t stop learning, because he was having fun.

Our students associate learning with misery. They associate learning with boredom. Frankly, us adults are the same. In his delightful book Feel-Good Productivity, doctor-turned-YouTube-guru Ali Abdaal wrote:

“Play is our first energiser. Life is stressful. Play makes it fun. If we can integrate the spirit of play into our lives, we’ll feel better – and do more too.”

And it’s true. Whenever you can make something a bit easier- maybe you’re taking that call in the bathtub or maybe you have The Office on in the background while you’re budgeting for the next month- you should consider doing it.

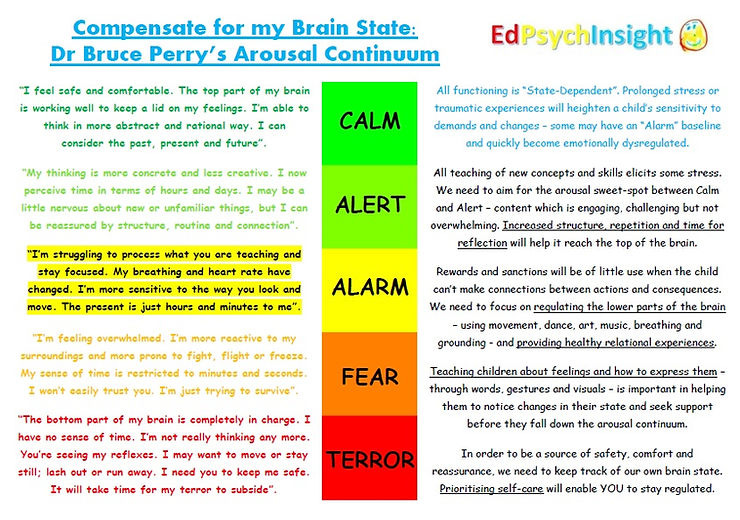

We know that things are easier for us when we feel relaxed and confident. We also know that students’ brains work better when they’re in a safe, secure, and stimulated emotional state. Again, as the benefactor of fantastic Professional Development courses, I’m familiar with the Arousal Continuum… and you probably are, too. If you, like me, read No Drama Discipline and you’re familiar with the phrases ‘upstairs brain’ and ‘downstairs brain,’ you know about the Arousal Continuum. A lot of Social-Emotional Learning curriculum is built on this model, actually, because it makes a bunch of sense and it’s easy to translate to student-friendly language.

The basic idea is that there are five different brain states dictated by our emotions, which take their cues from internal and external contexts and events.

In calm states, students feel calm and comfortable and regulated. Abstract thought happens here. The prefrontal cortex is in charge.

In alert states, students are drawn into more concrete thinking. Analysis brain is active. Students might be a little nervous about what’s to come, but that keeps them awake enough to focus on it!

In alarm, students are starting to become overwhelmed. Thought is moving away from the prefrontal cortex, and rational thought is giving way to instinct and reaction.

In fear, students are very reactive. The amygdala is hijacking the brain, sending it into a ‘run or fight now, think later’ state. Survival mode.

In terror, the amygdala has taken over entirely. Rational thought and response is out of the question. The person is entirely controlled by their reflexes.

Learning happens between calm and alert. Any more stress than that and students start losing access to the part of their brains that actually allows them to engage learning with rational thought. So maybe lashing out at students for making mistakes isn’t the best way to teach them how to think critically.

Maybe Raph makes more sense than he realizes. Boredom is the opposite of learning, but so are alarm, fear, and terror. Educators are familiar with Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development, the space between what learners can do on their own and what learners need help with. This has largely been considered the ‘sweet spot’ of learning. If it’s too easy, learners will find it boring. If it’s too hard, learners will go through a stress response until they decide it isn’t worth it, give up, and then it’s also boring.

Leading from a place of love means considering the students’ emotional states. It feels better and it’s more effective in the long-run. Yeah, sure, yelling at students and scaring them into getting good test scores is one approach for one year, but then they’re scared to even try next year.

Consider the implications for non-teaching leaders- what if your manager, supervisor, or administrator paid more attention to your stress levels and worked harder to minimize the barriers between you and success?

THE ACTION(S)

Let’s try something new, dear readership. I’d like you to take a moment to consider these questions and fearlessly leave a comment containing your answers using the button below.

First of all, think of something you’re dreading right now. Ask yourself “What would it look like if I made it fun?” Maybe you’re listening to Ace of Base’s 1993 North American debut album The Sign and dancing like a maniac while you’re doing dishes. I don’t know. (Not my first choice, but not my last, either). Now try it. Ali Abdaal would be proud.

Secondly, think about a supervisor, manager, or teacher that you really disliked. Where did they lead from- a place of fear, authority, expertise, or love? How did that make you feel? Did it change the way you think about the work you were doing in that situation?

Lastly, think about yourself as a leader, supervisor, teacher, or parent- where do you lead from, and how does it feel for you?

Thank you for reading. I didn’t mean to dump 1900 words onto a screen on a Tuesday night, but I probably really needed it.

I’m glad to have you along for the ride, reader. Until next week.